In the last five to 10 years, stakeholders from around the globe have launched initiatives aimed at better understanding how real-world evidence (RWE) can be used in decision-making. Multiple groups have published white papers, position pieces, recommendations, and guidance on how RWE studies should be conducted, and on how RWE can complement RCTs to complete an evidence package and inform decisions.

For researchers, it can be challenging to navigate all of these sources of information and distill best practices for generating decision-quality evidence. For regulators, health technology assessment (HTA) agencies, and payers currently working to define RWE standards, it is important to understand the current landscape of published best practices not only to avoid duplicate work, but also to facilitate harmonization of guidance across global stakeholders.

In a recent publication in the Journal of Comparative Effectiveness Research, we collaborated with co-authors from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), the European Medicines Agency (EMA), and Amgen to synthesize RWE recommendations issued by key stakeholders and identify areas where decision makers and researchers should focus their attention to collectively move toward comprehensive RWE guidance.

Goal of the study

We aimed to organize the existing RWE recommendations and identify points of consensus and gaps to provide researchers with a pathway to generate high quality RWE. In the paper, we discuss how decision makers can move from the current patchwork of recommendations to comprehensive guidance on RWE generation and use.

Process for the analysis

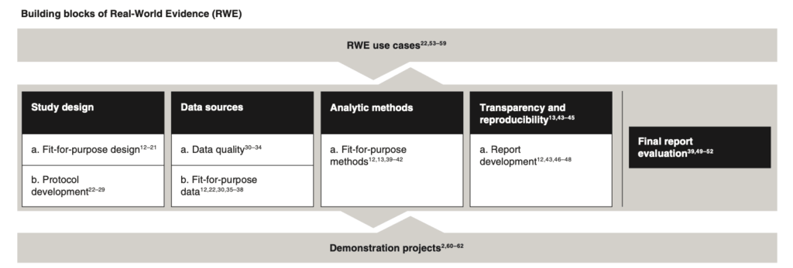

We completed a targeted grey literature search of key stakeholders—including regulators, HTA bodies, RWE research initiatives, professional organizations, and U.S. government organizations—to identify documents that discussed RWE generation or use. From these documents, we extracted the objective and any RWE recommendations. We then compared and contrasted the recommendations against each other and against what we considered essential for “comprehensive guidance.” Specifically, we propose that comprehensive guidance includes:

- A minimally sufficient, consensus-based justification or definition of the building blocks for decision-grade RWE and their components—for example, a definition of fit-for-purpose (FFP) data;

- A step-by-step process that researchers can follow to meet decision maker expectations; and

- A tool or checklist to aid researchers in determining whether their study meets all criteria, and to help communicate study design decisions to the decision makers.

Key findings

Organized structure for RWE recommendations

There were key themes in the recommendation documents, which we arranged into what we considered the “building blocks” of high quality RWE (see Figure 1 below). These themes followed the typical scientific process—from study design to final report evaluation—which were further supported by RWE use cases (i.e., what hypotheses were relevant for RWE studies?) and demonstration projects (i.e., research projects that inform or shape recommendations within a building block, such as RCT DUPLICATE).

Comparing and contrasting recommendations within a building block

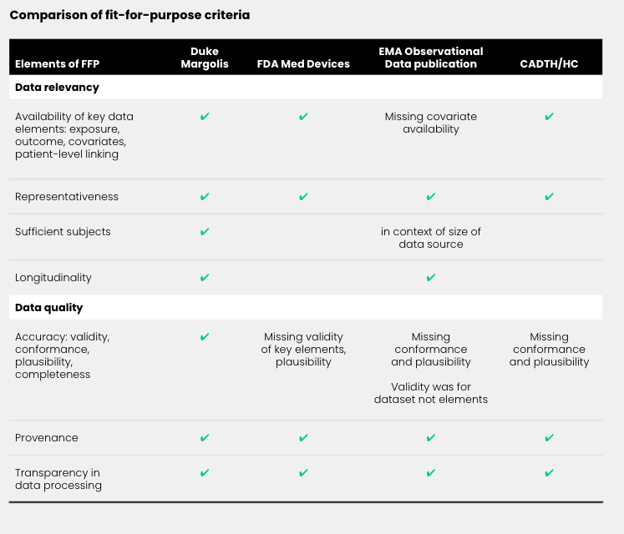

The building blocks varied both in the level of recommendation activity and in the level of agreement in recommendations between stakeholders. For example, in the “fit-for-purpose data” building block, stakeholders including regulators, HTAs, RWE initiatives, and independent researchers have contributed ideas around what defines a FFP dataset (see Figure 2 below).

While agreement between these recommendations was high, there was not a complete consensus on how to define FFP data. For example, the Duke-Margolis Center for Health Policy stated that the elements of a FFP data set include data relevancy and reliability, and that the availability of key elements like confounders is essential. The EMA generally agreed, but its recommendations excluded confounder availability in the data as a necessary element of FFP data. While this is likely a result of the objective of the EMA recommendation document (the document did not specifically set out to define FFP data), it is worth noting; researchers trying to determine how the EMA will evaluate their real-world data (RWD) selection could be impacted by the lack of specificity in EMA’s publications on the topic.

Comparing current recommendations to components necessary for comprehensive guidance

In addition to comparing and contrasting recommendations to each other, we compared the existing recommendations to what we would expect in comprehensive RWE guidance. We do not expect decision makers to provide researchers with an exact recipe on how to generate high quality RWE, but we do hope for guardrails that focus on important elements of RWE.

When we evaluated the existing recommendations against the criteria, we saw varying levels of completeness—for example, the “transparency and reproducibility” building block was most complete—but substantial gaps remain. While clear expectations on how decision makers define transparency do not exist (e.g., what are the best practices for engaging with decision makers on RWE studies?), the industry is moving toward a step-by-step process to ensure transparency in study design and execution, including protocol registration practices, tools, and checklists (e.g., the structured template for planning and reporting on RWE study implementation (STaRT-RWE)).

Looking ahead: Transforming fragmented recommendations to comprehensive guidance

We encourage stakeholders to use this analysis to identify and prioritize areas that would benefit from additional development efforts. While we strive to advance towards comprehensive RWE guidance, we’ve identified several next steps we urge stakeholders to focus on in the immediate:

- Strategically prioritize guidance development on areas that address RWE critics’ major concerns (i.e., working on building consensus among which tools are most appropriate for assessing transparency and data quality, and better capturing patient-reported outcomes and other potential endpoints within traditional RWD sources)

- Align on the definition of “high quality” RWE and offer consistent, comprehensive guidance for researchers

- Initiate demonstration projects to inform and accelerate progress toward more comprehensive guidance

Comprehensive guidance is necessary to define the best practices and standards that lead to high quality, decision-grade RWE generation. While the field has made substantial progress in defining some components of RWE, we’ve highlighted gaps that would benefit from additional demonstration projects and recommendations.

Generally, initiatives that support collaboration and consensus across various stakeholders would help expedite the development of comprehensive guidance. These standards would enable broader adoption of best practices among researchers, which would, in turn, lead to the generation of more reliable RWE that decision makers can trust to inform their evaluations.